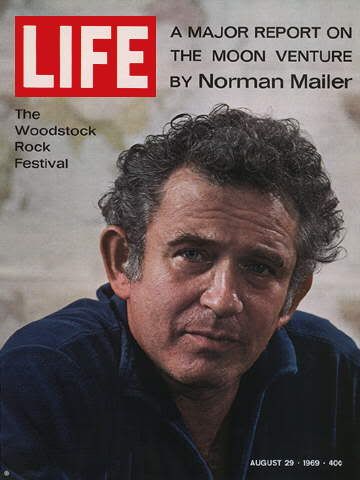

Norman Mailer died Saturday of renal failure at the age of 84, and the world yawned.

It's hard to overstate just how sad that is. Of the three truly famous novelists of the past few decades (Vonnegut, Vidal, Mailer) only Vidal is still puttering around, wheeling from campus to campus to gleefully assume his role as the bee in America's bonnet. There's just no contemporary comparison to those three's cultural importance--these were men who challenged the status quo, were hounded for (and gladly proffered) their creative thoughts on all the subjects du jour, and who became celebrities not by dint of luck or connections but by originality and talent. But writers today have assumed a more passive role, which may explain the media's relatively muted response to Mailer's passing, whose activist legacy seems particularly anachronistic nowadays. JK Rowling seems more content to cash her checks than take a strong stand. Thomas Pynchon won't even give an interview outside of his Simpsons bits. Stephen King can't be bothered to write about anything outside of the Red Sox. And how many of our generation has even read anything by Don Delillo?

But Mailer was something different, his legend born from the first serious post-WW2 novel (The Naked and the Dead, #51 on the Modern Library List, which means I'll review it here in, oh, three years or so). He wasn't an angel; he was a conservative prude and bully who thought that sex was designed for two consenting members of the opposite sex, and to consider any alternative was tantamount to making a lunch date with Lucifer himself ("Good fucks make good babies"). Mailer lived his life as a nouveau Hemingway, carousing with boxers and athletes (whose chiseled bodies presumably made him squirm) and embracing the fuzzy feelings of fermented beverages to an alarmingly destructive degree--in one drunken frenzy he stabbed and nearly killed his second wife, who demonstrated her fidelity by politely declining to press charges.

But he was also, improbably, deeply compassionate. His "Armies of the Night" was an empathetic description of a march on the Pentagon, published at a time where popular opinion was still firmly with the administration and its memorable capers in Indochina, sentiments Mailer fiercely derided to the point of being arrested for his anti-war activism. But that current of social consciousness was best expressed in the first novel of Mailer's I'd ever read, The Executioner's Song, a probing, 1500+ page historical novel detailing the last few years of Gary Gilmore's life. It's hard to imagine now, but there was a brief period in the 60s and 70s where grassroots organizing and prisoner's rights movements pressured the Supreme Court enough to actually bring about the abolition of the death penalty in 1972. Of course, this being America, that drastic action was swiftly overturned, and Gary Gilmore of Utah (natch) was the first victim of the death penalty's glorious encore in January of 1977.

It's hard to imagine now, but there was a brief period in the 60s and 70s where grassroots organizing and prisoner's rights movements pressured the Supreme Court enough to actually bring about the abolition of the death penalty in 1972. Of course, this being America, that drastic action was swiftly overturned, and Gary Gilmore of Utah (natch) was the first victim of the death penalty's glorious encore in January of 1977.

Through extensive interviews and letters, Mailer tried to re-piece Gilmore's life, not combing for a Rosebud so much as examining the nature of evil acts. In the process, Gilmore becomes not only a vicious criminal who ruthlessly butchered a motel manager deep in Mormon country, but an obviously tortured soul touched by madness, crafting beautiful letters to his girlfriend and lawyers (many of which were reprinted verbatim in the book) and painting canvasses alternating between exultant and disturbed. In a perverse conflation of guilt and pride and even fame-hunting, Gilmore ultimately refused to appeal his case in the wake of legal counsel suggesting that such an appeal would spare his life.

It takes a master's touch to undermine an audience's sensibilities without the aid of a blunt instrument, and it takes an awful lot of courage to depict a murderer as singularly human. Mailer possessed both but Hollywood seems intent on destroying such qualities, as handily demonstrated by the only "serious" look at the death penalty offered at a theater near you in recent years, The Life of David Gale, a comically bad sledgehammer of a movie. As the great American Writer--and, by extension, the Great American Novel--begin to solemnly fade away, so too will the various shades of gray that make all great art so timeless and world-changing.

The Executioner's Song is a rich tapestry of personal loss and conflict, of grief and madness, that ultimately eradicates the Manichean notion of good and evil so pervasive in our culture. That's a lesson that not even 3 years as the ward of the socially-conscious Jesuits could fully hammer home for me; Mailer did so in a couple of weeks. Not bad for a book idly chosen for its length to fill some dark winter nights. RIP, Norman Mailer.

Sunday, November 11, 2007

Norman Mailer and Me

Posted by

Steven

at

11:46 PM

![]()

Labels: activism, eulogies, literature, norman mailer

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

3 comments:

you write about things no one cares about, but you.

i have not made a decison to whether this is a good or bad thing, however, i'm sure it is of no importance to your self esteem.

despite this, your writing is absolutely eloquent.

Perhaps you can add your name to these greats. no one has ever made trashy bands sound so good.

i loved vonnegut. it was sad when he died.

What a hole is left by his passing. Your essay about him is perfect. I think even he would approve. Seriously.

Post a Comment